This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Christopher J. Chiu, MD: Welcome back to The Cribsiders. This is a video recap of a recent Cribsiders podcast. What are we reviewing today?

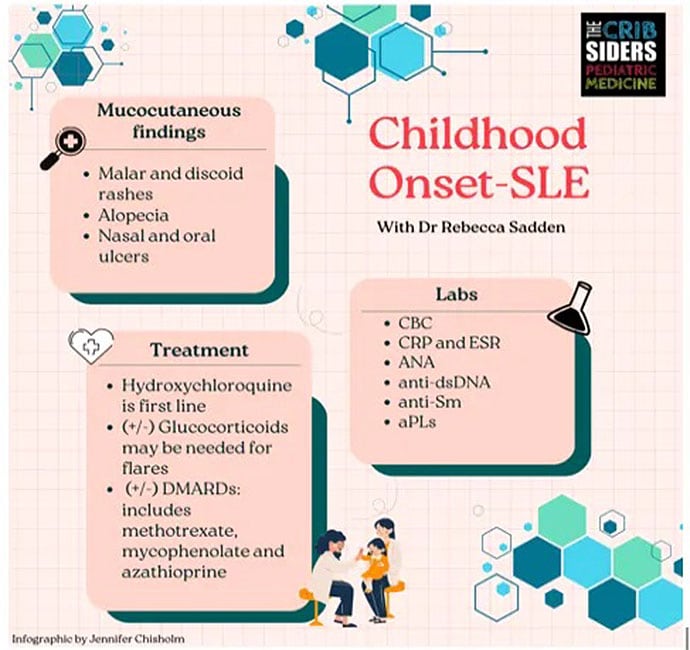

Jessica Hane, MD: We're here today to talk about childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). On Childhood-Onset SLE, our expert was Dr Rebecca Sadun, who specializes in pediatric and adult rheumatology at Duke.

Chiu: How do pediatric patients with SLE typically present?

Hane: This was one of the biggest take-homes for me. Patients with SLE can present with a fairly broad range of symptoms; it's actually a very heterogeneous disease. Fever, fatigue, weight loss, joint pain, and stiffness are the most common presenting symptoms.

Patients might also have a rash. Skin findings are present in about two thirds of children with SLE; they include a malar or discoid rash, alopecia, and oral or nasal ulcers. Dr Sadun advised us to think also about the presentation timeline. Symptoms that last hours to days are not really concerning for SLE, but if symptoms persist for weeks to months, lupus should definitely be on the differential.

Chiu: If SLE is on the differential, what initial laboratory evaluation is suggested?

Hane: It depends on where you are. In the primary care clinic, you can start with a CBC and inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate), because they tend to be abnormal in patients with rheumatologic conditions. To make a diagnosis of SLE, these five tests should be done:

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA)

Anti–double-stranded DNA (AdsDNA)

Anti-Smith (Anti-Sm)

C3 and C4

Antiphospholipid autoantibodies

If you can get a patient into a rheumatology clinic within a few days, it's reasonable to postpone this expensive workup. But if the index of suspicion is high and it's going to be months before patients can see a pediatric rheumatologist (and some states lack a specialist entirely), primary care and pediatric clinicians can start the workup.

Chiu: Are there certain patient populations that are more likely to have lupus?

Hane: Yes. Lupus is rare in children before the age of 9. But the incidence increases in early and late adolescence. There is also a predominance for females — about 3 to 1 (female to male) difference before puberty and 9 to 1 during puberty.

Certain races and ethnicities tend to have higher rates of SLE: African American, African, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Latinx populations tend to have higher rates of lupus. Although a family history of rheumatologic disease does raise the pretest probability of SLE, many patients diagnosed with lupus don't have a family history.

Chiu: So, let's say we have a high index of suspicion based on presentation and family history. We've done the laboratory evaluation. How do we make the final diagnosis of SLE?

Hane: We talked about a couple different criteria, but Dr Sadun told us that the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) 2012 criteria tend to be the most commonly used in pediatric practice. The general clinical criteria for diagnosing SLE include mucocutaneous manifestations, serositis, joint disease, signs of PTSD, hemolytic disease, renal involvement, and CNS involvement.

Chiu: Let's talk about treatment. What medications should we be starting?

Hane: Every patient with lupus should be on hydroxychloroquine if they can tolerate it, because it helps prevent flares. However, if a patient is having significant symptoms and you need something to work quickly, then think about starting steroids. And then as soon as you start steroids, you're thinking about what medications you can use to get the patient off steroids. Those are disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The most commonly used DMARDs in pediatric lupus are methotrexate, mycophenolate, and azathioprine.

Chiu: Can you clarify something else that came up on the podcast? What is a SLEDAI score?

Hane: This is the systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index. It's actually a tool to help stratify disease severity and guide therapy. It's primarily used by pediatric rheumatologists.

Chiu: That's a good one. Do you have any final pearls or takeaways on this topic?

Hane: We learned that infection is one of the highest causes of death in patients with lupus. So as a primary care doctor, one of the best things you can do is make sure your patient is up-to-date on routine vaccines.

Another big take-home point is that ANA is a very useful test if your index of suspicion is high. It's very sensitive, but not specific, for lupus. About 10%-15% of healthy children will have a positive ANA test. So, if your index of suspicion is low for lupus, you shouldn't order an ANA.

Chiu: Thanks again for joining us for another Medscape video recap of The Cribsiders pediatric podcast. You can listen to the full pisode and others on any podcast player or at www.thecribsiders.com. Thanks for tuning in.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image: Jennifer Chisolm/The Cribsiders

© 2023 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Christopher J. Chiu, Jessica Hane. When You Suspect Lupus in a Child - Medscape - Jun 13, 2023.

Comments